And maybe what I’m understanding more and more as I get older, is that music like Kate Bush has really influenced me. But as a music nerd, I just had to follow my heart, and my heart was those beats that were happening in England. We all run this label in Iceland called Bad Taste, and they’re still like my best mates. I love the people in it-we still text each other all the time. But I think what happened to me-the music in the band I was in wasn’t my taste. When everybody is kind of equal, and opened-up, and the clocks go away, and there’s just a sort of flow. I don’t know what it’s called in English. I really love, and get high on, when there’s a flow in a group, sort of energy.

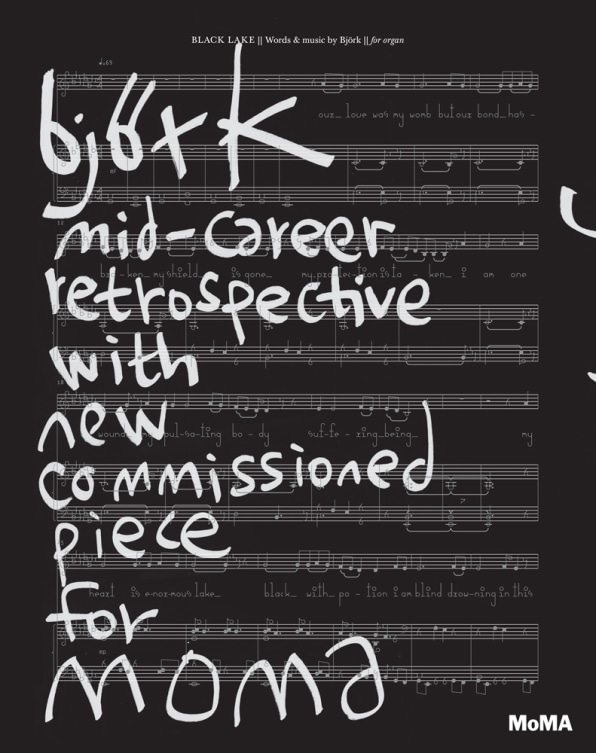

But then as I got to know Nellee, we slowly just did the whole thing together. I actually started working with Graham Massey, from Manchester. I didn’t know at the time that he would end up producing it-it was one of those things. And I’d met Nellee Hooper, who was the producer of the album. I had met Dom T, who was a DJ and my boyfriend at the time. And then it wasn’t til ’93 that I moved to London, had that white fluffy-I wore this all the time, white mohair, like a bomber jacket. I started going to raves a little bit back in Manchester in ’89, hanging out with 808 States and Graham Massey. And I just found that all the people that were exciting me musically were living in London and it was just a mission I really had to go on. I moved with my son, he was 6 at the time. It’s very much when I moved first to London-I was a bit crazy, a single mom. The camera was literally like this big-so you get all these details. Here, she weighs in on 12 of the most arresting works to be displayed at MOMA. (The other two are in Iceland and London.) Sipping tea and wearing a bright white parka, platform nurse’s shoes and a brilliant yellow dress that seemed decidedly springlike on a gray winter day, Björk was typically specific and eloquent about what inspired the images that photographers, directors, costumers, fashion designers, graphic designers and makeup artists have crafted for her.Įach is part of its own chapter in Björk’s impressive catalog of musical identities. She chose a small cafe on a hidden-away street in Brooklyn Heights, where she keeps one of her three homes. The singer sat down with TIME a few weeks before the retrospective was scheduled to open at MOMA. “To take someone on a musical journey, like a musician’s development, how you change in 20 years’ time. “It’s tricky for a musician to be in a visual museum,” she says. Biesenbach pursued the singer for five years before she agreed to the retrospective. The installation at MOMA, on display from March 8 to June 7, spreads over three floors, encompassing the photographs, music videos, costumes and custom-made instruments that have helped make Björk, 49, a singular pop presence since she emerged from Iceland with the Sugarcubes in 1987. To accommodate the resonating bass notes in a specially commissioned video for “Black Lake,” a song from Björk’s latest album, Vulnicura, “we had to build a new floor,” Biesenbach says, “to keep our Picassos from falling off the walls.” So when curator Klaus Biesenbach set out to exhibit the Icelandic iconoclast’s voluminous portfolio of visual and sonic art, he had to modify the building. New York City’s Museum of Modern Art wasn’t designed to readily accept the life’s work of Björk Guðmundsdóttir-a trait it shares with most of the world, which isn’t always inclined to embrace music that is challenging, vibrant and on occasion utterly outside the realm of mainstream pop.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)